Listen with Me: Small Doors, Hand Sanitizer, God

Margaret Schnabel

I’m on a walk in Jericho—the neighborhood that flanks the northern edge of Oxford, England, where my partner lives—and I see a large, ancient-looking door bridging the gap between two houses. There’s a smaller door carved into its bottom right side, just big enough to fit one or two people through. The visual effect, I must admit, makes me laugh: it’s as if the owners of the houses had carefully crafted a palatial, imposing image of themselves and then thought, oh, shit. I find myself wondering how often they open the entire door.

Grandeur like that often feels foreign to me—prohibited, somehow. Every time I sit down to write—to open a big, grandiose door of an idea—I tell myself that, just this once, I’ll open a lot of small ones instead: I’ll flesh out a set of bullet points into barely-grammatical sentences. I’ll tweak those sentences for clarity. For structure. For style. And then somehow I’ve eked my way through the big door without ever, it seems, confronting it head on.

For a small-door aficionado such as myself, capital-S Spirituality is especially hard to approach without feeling awkward, ungainly, unwelcome. I’ve never had a formal religious practice. Spiritual moments come instead in small, unexpected snatches: walking home late from the library and hearing a live concert down the street, feeling my brain smooth out a little bit more with each chord. Seeing a baby bird crushed onto the sidewalk outside of my house, the still-rising sun skating over its little wings. Lighting all of the cheap candles that my partner and I own, spreading a plastic picnic blanket on his floor, and scooping out honeydew melon halves with our hands. Watching the girl sitting across from me at the student union—hearing her heavy, steady breaths filter through her mask as she scrolls through her phone. The iced coffee next to her nearly the size of her head. Glorious.

I admire the artists we’ll be listening to—Okay Kaya, Phoebe Bridgers, Julien Baker—for their ability to create those small, unassuming moments that reverberate in my head for days afterward. They make bigness out of what they have around them, which is what I have around me, which is smallness, plain and mundane.

In a recent piece for the New Yorker, Jia Tolentino notes something similar: “Over the last couple of years, a wave of young female indie singer-songwriters has been releasing a sort of music that I have started to rely on, as if its sound were an inner tube on a choppy river, something I could rest on, turning my face to the sun.” Maybe we can’t hope for the big-door spirituality, listening to these artists together—but perhaps something buoyant and pliable is all we need.

LISTEN ALONG WITH ME

- Okay Kaya, “Palm Psalm”

- Phoebe Bridgers, “Graceland Too”

- Julien Baker, “Appointments”

Okay Kaya, “Palm Psalm”

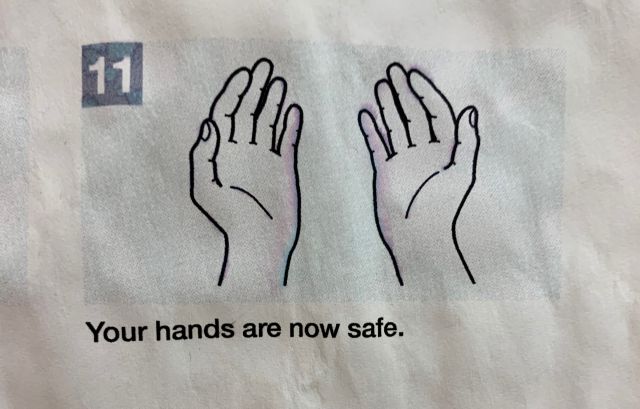

After an extended intro, Okay Kaya’s voice emerges, gravelly and close, to alert us that “around 20 seconds have passed.” In fact, exactly twenty seconds have passed—and I’m reminded of the meaning that that seemingly arbitrary unit of time has accrued over the course of the past year. Twenty seconds of hand-washing will keep us safe, protect us from each other.

Twenty is virtuous, now—another entry in our ever-fluctuating array of numbers made meaningful. We seek out holy trinities, lucky sevens; we refuse to build thirteenth floors. But our very human insistence on drawing patterns, on telling a story, can hurt us. In her newsletter Griefbacon, Helena Fitzgerald writes that anniversaries are only happy because we will them to be so:

Anniversaries are dangerous in the same way very beautiful days in the late spring and early summer are dangerous, heavy with too much meaning and offering too much permission. […] [It’s that] immature and stubborn reaching for meaning that compels us to celebrate anniversaries, to insist on their significance, to throw up a holiday in place of the natural sadness that comes with these reminders of accumulating time, trying to pretend that loss is actually abundance, and that regret is in fact joy.1

When I think about religion, I think about mitigating the pain of the inevitable fact of loss and grief—of confronting the small, sad ends of our lives by insisting that there is something divine, something Else, something to thread all of this through with meaning.

And sometimes we don’t want that meaning handed to us. “The last time I took something from a stranger, I thought it was a note,” Okay Kaya grins next. “But it was a pamphlet with a prophet some of us know.” It’s funny to me how something so necessary, so urgent to one person can curdle when handed to another; how one can want a mundane human interaction and instead receive the divine, unasked for, unwanted. At music camp one summer when I was eight or nine, a girl asked me, insistently, if I’d been “saved.” I didn’t know what she meant, but her tone was urgent, and I wanted her to like me, so I wavered, nodded, whispered a yes. She probed—“when?”—and my stomach sank, my face flushed in the Southern humidity. I hadn’t been saved. I hadn’t known I needed to be saved.

Later, she insisted on handing me a brochure, inside of which was a quiz: “ARE YOU DESTINED FOR HEAVEN—” (ice-blue letters with a halo on top) “—OR HELL?” Looking at those words made me shudder; there was a possibility, I knew, that if I took the quiz I’d fall on the wrong side of those letters.

Eventually, my mom tugged me back to the icy haven of our room and slipped the brochure into the trash can.

“Purity Purell,” Okay Kaya sings: “praying my dry palms together.” It’s the whole conceit of the song, I know, but I love how her puns probe the relationship between cleanliness and purity. On the micropod “Hey, Cool Life!”, Mary HK Choi talks about washing her face as soon as she gets up; otherwise, she admits, it’s as if she is saying to herself that she doesn’t deserve to be clean—that she’s a dirty, worthless person. As soon as she said it, I felt it in my core. All of these things get spooled together, whether we want them to be or not: cleanliness, wealth, moral purity. Virginity is divinity; to transcend, we must be untouched, detached from the messy world of human desire.

Phoebe Bridgers, “Graceland Too”

I’ve always loved the way that this song positions driving as a solitary, almost ritual practice:

No longer a danger to herself or others

She made up her mind and laced up her shoes

Yelled down the hall but nobody answered

So she walked outside without an excuse[…] So she picks a direction, it’s ninety to Memphis

Turns up the music so thought don’t intrude

Predictably winds up thinking of Elvis

And wonders if he believed songs could come true

Driving has never felt like a ritual to me: I’m too suspicious of my own inevitable failings on the road. Last week, in the parking lot of a LabCorp, I slumped over in the driver’s seat of my car and awoke with my chin on my chest, a shrill ringing in my ears. I’d just gotten my blood drawn, and made it back to my car only to faint, alone, my door still cracked open. When I came to, the left side of my face was wet with rain.

I looked it up later and discovered that fainting is a body’s attempt to calm itself down by slowing the heart rate, swinging too far in the opposite direction towards a hard-reset kind of calm. My body had been trying to protect me by shutting down. It had also been trying to protect me with the pain signals that had prompted the doctor’s appointment in the first place: a strange tingling that stretched from my fingertips up through my wrists and forearms, later unglamorously revealed to be carpal tunnel.

I know I’m not alone in neglecting my body for the unceasing demands of digital life. The word “digital” has its roots in the Latin digitus, for “finger”—so perhaps it’s no surprise that so many of us are destroying our hands as we tick through our never-ending to-do lists. It’s compulsive, this need to squeeze accomplishment out of every part of our days.

In a podcast episode for The Cut, Esther Perel observes that secularization and the rise of the individual have provoked a kind of spiritual poverty that we seek to fill through our work and romantic relationships:

We look to work today for belonging, for identity growth, self-development, for purpose, for meaning, for community. […] Love and work have become the hubs where we actually go to fulfill some of our most important existential needs. We want passion in both, we want to become the best versions of ourselves in both.2

But when we use work to structure our identities, she notes, we are almost never able to meet the demands we have for ourselves:

When work is the place where you outdo yourself, where you search for self-worth, it becomes unrelenting. If work structures your life to that extent, then the inability to meet the demands will translate into burnout.3

When we enshrine individual success to such an extent—when it structures the very rubrics by which we measure meaning in our lives—something weird happens. We both crave and feel beholden to the approval of some larger-than-life “society” that lurks beyond our desks, ready to judge our every keystroke, and feel reluctant to truly give ourselves over to that society, because it takes time, energy, resources away from our own work.

A friend wrote to me in a letter early last spring: As someone who grew up outside the church, where did/do you find places of accountability?

I’m still thinking of my response. I’m worried that my real answer would fall in line with the way the same friend described college campuses:

In a lot of ways I feel like the traditional American college experience really destroys a lot of community accountability—we’re taught to think constantly of ourselves, our futures, what we want. […] But how on earth can we exist in a community & hold one another accountable in that way?

In a recent edition of her newsletter “Culture Study,” journalist Ann Helen Petersen posits that truly existing in community with one another means giving up many of the individual freedoms that the modern era has made us reluctant to relinquish:

We recognize that systems of care and community are broken, and want to build them otherwise. We want dependability, we want intimacy, we want to spread burdens and celebrations across a wider swath of people. We want something else. But we have also been well-trained to resist inconvenience, even of the mildest sort: I want what I want, I want it this way, and at this cost, and I want it now.4

Maybe it’s why I’ve felt a strange tug recently to make my weekly grocery run with my roommates, even if I could do it more efficiently, or less self-consciously, on my own: I want community. I want to share the burden of routine domestic tasks, however small and inconsequential they each are.

Most of Bridgers’ music feels solitary to me—protagonistic. But this song is folksy: not the cool blasé solitude that indie singer-songwritertude usually accrues, but a big community of banjos plugging away, earnest drum beats marching the whole enterprise along, saccharine fiddles skating over the top. This might, admittedly, be the new cool; I think of the “cottagecore” trends on TikTok, Gen Z’s recent fascination with the slow, rural, and domestic as a kind of natural pushback to their tech-saturated upbringings. But I’d like to think that there’s a little bit more to it than that—Bridgers’ own recognition that it takes a community to produce a song, and a person, and that community is enmeshed in the fabric of it all, quietly undergirding those claims to solitude.

Two years ago, it would’ve been tempting to yoke my own idea of spirituality to coolness: to compare a house show to a church service (about which I still know very little), deify the routine pounding of bass and swaying of sweaty bodies into ritual. Write about the yowling singers leading us out of the reeking, shadowy basement and into transcendence.

But the truth, now that I let myself see it, is that I often felt alone at those house shows. I watched people feeling transcendent, feeling like protagonists, feeling absorbed, but I never felt it myself.

I’ll never forget Phoebe Bridgers’ admission in Song Exploder that, sometimes, her voice sounds too emotional on its own; it needs to be doubled against itself to hollow out some of its earnestness. (I think of the icy smoothness of a mirror saying this is a reflection, this is artifice, trust me—of how and why we find irony more believable than confession.)

In “Mirror,” Sylvia Plath captures that icy smoothness, highlighting the ways in which a mirror’s exactness haunts us:

A woman bends over me,

Searching my reaches for what she really is.

Then she turns to those liars, the candles or the moon.

I see her back, and reflect it faithfully.

She rewards me with tears and an agitation of hands.

I am important to her. She comes and goes.

Each morning it is her face that replaces the darkness.

In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman

Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.

I love that image—“a terrible fish”—but I don’t fear losing my youth. My partner reminds me sometimes that this is a time in my life I’m supposed to enjoy, and the concept feels so foreign to me. My generation is full of youth-squanderers—not in a glamorous ’70s Dazed and Confused way, but in a too-trapped-in-our-own-anxiety-to-pick-up-the-phone kind of way. “Enjoying our youth” is just another unchecked box.

Julien Baker reminds me of that.

Julien Baker, “Appointments”

To the uninitiated, “Appointments” sounds like a sad song. As Baker explains on Song Exploder, however, it’s a happier, major-key progression of the album’s opener.

“I’m staying in tonight,” Baker sings:

…It’s just that I talked to somebody again

Who knows how to help me get better

Until then I should just try not to miss anymore

Appointments

Baker’s not alone in highlighting the absurdity of the mundane things we have to do to address what feel like giant existential problems. More often than not, however, it’s exactly these small, cheesy, pointless, unglamorous steps that have helped me sit with those big-door things: writing down a thought and picking out its cognitive distortions, paying attention to my senses, taking a walk. During the most physically panicked time of my life, one therapist suggested that I buy a fidget toy.

I guess it’s my begrudging faith in the value of these infinitesimal steps that makes me feel inevitably detached from Real, True Transcendence, despite the hundreds of millions of people who think and live otherwise. Religion’s pretenses to a grand divine scale—its promises of opening the big door—never felt like something I could earnestly believe in, ever-conscious as I am of my (and, by extension, other people’s) embarrassing tiny humanness.

But is that actually the truth? Or have I been taught, as a woman, to minimize my big-door aspirations, to deny that I’ve ever earnestly sought transcendence? Kelli Korducki calls this brand of female self-censorship “Liz Lemoning,” after the offbeat heroine of 30 Rock:

…the character embodied an archetype that’s now widely recognizable, reproduced again and again in women (always women!) that we see on the screen and in real life. […] She probably isn’t your boss, but she might be your fast-rising co-worker — the one whose viral tweets project a chaotic energy that doesn’t quite track with the focused deliberation you observe at the office. The Hot Mess is likely attractive and successful, typically in a creative field, but she’s just bumbling enough to be “relatable” (that is, “nonthreatening”).

If we admit what we have, it will be taken away—or, at the very least, cheapened. Maybe I’m reluctant to write about my nascent spirituality because dragging it into the harsh light of a published essay will almost certainly destroy it. My spiritual moments are still little sprouts; they feel cheesy to write; I don’t want to line them up neatly into a narrative.

Maybe I’m nervous that I don’t own them, yet, or that I never will. But there’s that word, own—as if anything in this life could ever be the providence of one person alone. Spirituality is like a porous filter through which we relate to one another and the world around us. I don’t have a religion, no. But I encounter it, in the world, in other people. And that can’t be cheapened.

Maybe it’s also true that I do search for the big doors—through music, through literature, through my relationships. Maybe the idea that I’m content with small doors is itself the pretense, the sham. Maybe we’re all wired to reach for the big stuff, inevitably.

“Maybe it’s all going to turn out all right,” sings Baker, “and I know that it’s not, but I have to believe that it is.”

Further Listening

- “Amelia,” Joni Mitchell

- “September,” Ayoni

- “Thinning,” Snail Mail

- “Boyish,” Japanese Breakfast

- “Me & My Dog,” boygenius

- “Black Dog,” Arlo Parks

- “Charlie,” Mallrat

- “00000 Million,” Gordi

- “Every Woman,” Vagabon

- “Allison,” Soccer Mommy

- “The Night Josh Tillman Listened to My Song,” Samia

- “I Wouldn’t Ask You,” Clairo

Footnotes

-

Helena Fitzgerald, “golden hour,” Griefbacon, March 3rd, 2021, https://griefbacon.substack.com/p/golden-hour ↩

-

Esther Perel, “We Are All Burnt Out,” The Cut, April 14th, 2021, transcript accessed via https://www.thecut.com/2021/04/the-cut-podcast-we-are-all-burned-out.html ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

Anne Helen Petersen, “Consider the Quasi-Commune,” Culture Study, March 14th, 2021, https://annehelen.substack.com/p/consider-the-quasi-commune ↩