BLESSING FOR FAGGOTS

Shawn Coughlin

i. blessing

(please read aloud)

Blessed be He in homosexuality! Blessed be He in Paranoia! Blessed be He in the city! Blessed be He in the Book!

Blessed be He who dwells in the shadow! Blessed be He! Blessed be He!

—selection from Kaddish, Allen Ginsberg (1961).1

ii. introduction

When I discovered that our spring theme was spirituality, I couldn’t help but recall the age-old adage: GOD HATES FAGS. Spawned from Fred Phelps’ wretched mind, the slogan stages homosexuals as an enemy inherently opposed to divinity. I remember seeing it plastered across my television as the Westboro Baptist Church protested against marriage equality in 2013. However, while trudging through their website, I discovered a slogan that seemed to scramble the chain of meaning implied by GOD HATES FAGS. This one reads: ‘CHRISTIANS’ CAUSED FAG MARRIAGE. ‘Christians’ caused fag marriage.2 Like, what?

The slogan places two seemingly opposed figures, Christians and fags, into a surprising alignment, and although I hate to credit bigots, I can’t help but find the phrase fascinating. Not only does it make an outrageous claim, but it sets homosexuality in correlation with religious practice, a gesture that contradicts their more famous slogan GOD HATES FAGS. Well, which is it, Fred? I want to ask. Does Christianity reject fags or does it make them?

And then it hits me. However ridiculous it sounds, something about the WBC’s paradoxical logic strikes me as unexpectedly familiar. Namely, that the tension between the two slogans reminds me that despite the abuse queers suffer at the hands of religious institutions, many of us, myself included, betray a funny habit of reengaging with spirituality—if not always via these same institutions.

But honestly, I’m not so sure how to embrace the spiritual. I’m self-conscious. A vague concept of spirituality winks at me from across the bar and I am both suspicious and attracted. In the words of poet Christian Wiman, I am an “unbelieving believer,” a person “whose consciousness is completely modern and yet who [has] this strong spiritual hunger inside them.”3 As others in this collection will attest, thinking about spirituality does not always come easily to those seeped in secular realms. Whether through abuse or instruction, many of us have learned to treat the spiritual as a suspicious category that must be contextualized, unpacked, or abandoned in favor of one’s safety or critical perspective.

In Margaret Schnabel’s essay “Listen with Me,” she acknowledges the difficulty of trusting spiritual modes of experience, even when they are grafted onto secular objects and rituals. She writes:

Two years ago, it would’ve been tempting to yoke my own idea of spirituality to coolness: to compare a house show to a church service… But the truth, now that I let myself see it, is that I often felt alone at those house shows. I watched people feeling transcendent, feeling like protagonists, feeling absorbed, and I never felt it myself.

The metaphor that intends to bind church services to a house show is tenuous; it can’t truthfully do what Margaret wants it to. The house show fails to confer the spiritual significance that would transform secular aesthetic experience into a proper analogy for our displaced spiritual consciousness. When preparing this essay, I similarly considered exploring spirituality via a secular tenor (namely, a psilocybin fueled romp through West LA). But when I started writing, I hated it. I caught myself inflating my own experiences just to get something written when really, there is absolutely nothing sublime about taking a bunch of drugs to walk around gleaming storefronts and tourist traps. Whenever I feel close to a ‘spiritual feeling,’ I can’t help but slip outside myself, up against the moment rather than inside it; I experience a proxy spiritualism that is more defined by “a unifying structure of against”4 than feelings of transcendence or comfort.

When Phelps’ words first came to my mind, I was embarrassed. Like, what the hell? Why is that my frame of reference? Why am I cheating myself out of a relationship with the sacred when I’m desperate for what it could offer? In Depression: A Public Feeling, Ann Cvetkovich describes the critical role of spirituality in confronting the physical and emotional devastation produced by histories of homophobia and colonization.5 Spirituality, she suggests, represents a way of being and knowing that can organize disparate and contradicting experiences under a unified strategy for navigating the world. It can connect us with subjects and histories that are otherwise inaccessible, absent, or destroyed, as well as help us engage with what is already present.

What I need, then, is a recalibration of ‘spiritual.’ Not a more specific definition, but a more satisfying and embodied understanding of the category as a whole. The aesthetics and feelings that often animate the sacred (i.e. transcendence, beauty, sublime, faith, certainty) cannot account for our experiences of the spiritual as ambient, banal, cute, disappointing, self-conscious, and so on. I say this not to invalidate the former mode of spirituality, but to understand how it is complicated by our other attachments.

In an attempt to make spirituality more accessible for myself, this essay works as a kind of mini-archive that imagines how homosexuality, grief, and the ordinary can accrue their own set of spiritual practices and meanings. It draws together blessings, critical readings, and personal essays to imagine how queer artists and scholars can engage with the spiritual by redefining where it lives, what it contains, and what it can accomplish.

iii. eroticism, habit, and spirituality in Louis Fratino

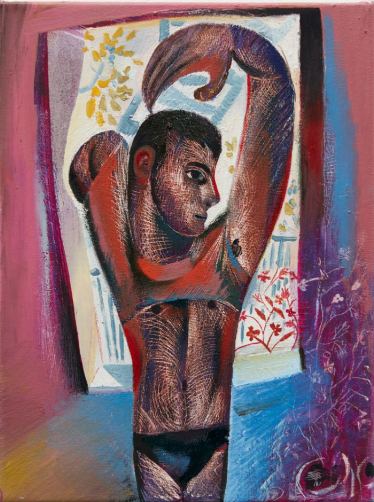

In his recent exhibitions, Morning (2020) and Come Softly To Me (2019), Louis Fratino offers a sensual and erotic portrayal of his everyday life as a gay artist. Adopting a modernist painting tradition, Fratino depicts vibrant interiors and cityscapes populated by lovers, friends, dishes, and the like. There is a lot of waking up and falling asleep, daily rituals performed naked under morning and moonlight. And although we may not immediately associate modernist painting or queerness with the sacred, Fratino’s work conjures the possibility of a homosexual spirituality—revealing to us how the spiritual is embedded within everyday feelings of queer desire.

The eroticism of Fratino’s work is sensational (in both the celebratory and felt sense), with paintings like Getting Dressed and Invitation seducing our hands as much as our eyes.6 Paring sexual imagery with expressive brushwork, these images present eroticized subjects richly textured with thin licks of body hair and swirling musculature. Their abundant materiality invites us to rub, scratch, and hold their bodies as though we are their lovers. We are compelled to engage with them through our bodies, placing ourselves within their fields of erotic sensation—the curve of his back, his hairy thighs, his warm skin.

On top of sensational eroticism, Fratino’s paintings emphasize the marking of habitual time. “A lot of the works are from memory,” he suggests, ”so I’m trying to remember the atmosphere or the feelings from a particular time.”7 May and July, for example, present regularized morning rituals such as bathing and defecating, while The Manhattan Bridge depicts one of Fratino’s nightly strolls through New York City.8 Similar to the Impressionist tradition, each image marks a precise moment by rendering not only time-specific rituals but particular variation in morning and evening light. When seen together, these images transform daily, habitual acts like walking and bathing into sensorial snapshots that capture the movement of time.

At the heart of Fratino’s work is an embodied gay eroticism sewn into the habitualized flow of everyday temporality. Even the title to pieces such as Waking up first, hard morning light, collapse time and homosexual eroticism into one phrase, as the erotic feeling of waking up “hard” overlaps with the “hard morning light” that slips through the window and marks the passage of time.9 His work brings to mind Elizabeth Freeman’s notion of erotohisotirography, which, “sees the body as a method, and historical consciousness as something intimately involved with corporeal sensations.”10 For her, the past is not behind us, but always already part of the present as a force that shapes queer bodies through both pleasure and violence. Fratino similarly offers the homosexual body and its pleasure as a way to record time, constructing his personal history through an archive of remembered erotic feelings rather than via a chronological timeline.

Upon first viewing Fratino’s paintings, I was thrilled by their ability to register temporality not only through time-based content but an embodied homosexual desire. However, to ignore the spiritual resonance of Fratino’s work is to lose out on its most exciting implications. It is, unfortunately, not surprising that this feature escaped my initial consideration of Fratino’s paintings. As stated in the introduction, my relationship with spirituality is frequently complicated by religious institutions that regularly dispense violence, suspicion, and rejection onto queer subjects. And yet, despite this, breaking from these institutions is hardly a seamless effort. For example, after she is excluded from partaking in the Holy Communion, lesbian scholar Ann Cvetkovich describes an unusual sense of sadness and relief stirred by her strained proximity to ritual practice:

Disappointed, I retreated to my corner. As the mass continued, I found myself quietly weeping, wrought up by the combination of ritual and rejection. The weeping was not really attached to any feeling or situation, and it was accompanied by a sense of sweet and gentle relief, as though something inside me had been opened and released and my personal sadness was not mine alone.11

Cvetkovich’s anecdote captures the ambiguous mixture of sadness, mania, and relief generated by queers (dis)engaging with the sacred. Her scholarship underscores what I see as a deeply recognizable relationship with spirituality where feelings of attraction, relief, shame, and rejection all congeal in our experiences with the sacred.

Despite the name calling, the belittling, and the sad violence, I find myself sneaking back to spirituality much like Cvetkovich does. As a teenager who feared the solitude of home, I disappeared among the boys who populated after-school religious programs. Bible studies, YoungLife, prayer groups. Their discussions of divine feeling and sacrifice melded marvelously with my hunger for “big questions” and homosexual flair. During prayer, I recall lifting my head as the other boys bowed theirs in holy meditation only to catch another face staring back at me. Exposed, lost, disinterested, our eyes meet for a brief moment. Why hadn’t he prayed with the rest of the group? He seemed familiar with its participants, knowledgeable of the stories, and even a leader among the other boys. After seeing each other we said nothing. I later discovered he had been outed and removed from religious leadership weeks earlier.

It is perhaps because of this hot-and-cold relationship with religious forms that I didn’t recognize the spirituality of Fratino’s work until more recently. While scrolling through the e-catalog for Come Softly to Me, I was struck by an image that I typically overlook when viewing the collection. Significantly smaller than Fratino’s other works, Angel Writing a Letter portrays a winged naked man (potentially Fratino) bent forward in contemplation as he prepares a letter.12 Here, Fratino embeds embodied homosexual eroticism within a habitual act of spiritual labor—in this case, writing a letter. Although an altogether mundane habit, here epistolary work is imbued with spiritual significance because it is literally presented as divine labor, locating the sacred within the everyday act of writing. As Cvetkovich suggests, “The sacred is connected to everyday practices that are not glamorous or other-worldly,” but instead situated within banal rituals such as daily composition.13

Fratino then infuses the spiritual act with homoeroticism as the angel—with his face lowered and his seat raised—assumes a position somewhere between bottoming and prayer (the former of which appears regularly throughout Fratino’s work). At the tip of his arched back, textured streams of color extend from the angel’s anus, as though the ordinary spiritual practice of letter writing has activated an embodied erotic sensation. Wheather it is absorbing or expelling the explosion of line and color, the anus is transformed into a channel through which a kind of mystical energy travels through the homosexual body.

Far from rejecting sacred objects in favor of secular imagery, Fratino receives the sacred as a sexual partner, literally presenting his ass for celestial bodies in pieces such as Blowjob and Moon.14 The erotic queer body thus represents an intereface for registering a relationship with spiritual experiences.

iv. harden

Kevin and I are visiting his father’s grave. It bears his name in stone, Timothy Masters, inscribed above an engraved sailboat and lighthouse. Although I never met Tim before he died, I’ve come to know him in a few ways. He is Kevin’s father as well as his father’s absence. He is a soft man and a pervert and the grandfather of Issac and Emma. He is opening gifts. He is Kevin’s good days and his bad ones.

Standing there, Kevin softly cries while I hold him. He misses Tim. We fall into each other as his beard rubs against my neck. His belly against mine. The feeling of holding him as he thinks of holding Tim. Him, Tim, and I. Holding Tim and holding each other. When we pull away I notice that he and I are hard and I say so. It somehow feels fitting. Tim, who left his porno, his perversion, his raunchy 80s movies, and his clitoris loli, now the site of our mutual tumescence.

Whenever we visit, I remember that moment and wonder if Tim had something to do with it. Am I trained to grow at the feeling of Kevin’s body, or was grief somehow part of our excitement?

v. ghosts

If Fratino offers the homosexual body as a channel through which spiritual energies progress, then visual artist Nguyen Tan Hoang shows how this progress is ultimately disrupted for queer bodies marked by racial violence and erasure. Unlike Fratino, whose work highlights the flow of spirituality through an everyday homoeroticism, Hoang emphasizes a spiritual practice of stops and skipages that upset the forward motion of time. His film, K.I.P. (2002), illustrates not only how erotic pleasure is tightly bound to grief, but how the spiritual turned spectral can disrupt and defamiliarize linear temporality.15

In K.I.P., Hoang’s ghostly image haunts a recovered VHS copy of Kip Noll, Superstar: Part 1—a compilation of gay porn star Kip Noll’s greatest scenes from the 1970s. When he initially viewed the film, Hoang describes discovering drop-outs and glitches in its audio and visuals, effectively marking where past viewers had damaged the tape by pausing, rewinding, and replaying the film’s “hottest parts.” Between these interruptions, Hoang overlays a pale, translucent video of his own moaning face, as though we are witnessing his image reflected on the same glass screen that Superstar was originally viewed through. The effect is disturbing and otherworldly, producing the uncanny sense that the artist is in fact hovering just above your shoulder, staring slack-jawed and wide-eyed at the distorted footage before you.

What are we to make of this ambiguous expression? As Freeman notes in her work on queer temporality, Hoang’s face registers an unusual overlapping of grief and pleasure.16 On the one hand, his moaning may allude to the satisfaction extracted from viewing gay pornography—particularly from a time “when urban gay men in the 1970s and early 1980s could enjoy casual sex without latex.”17 On the other, his expression also mourns the death of this very same moment in a world overwhelmed by homophobia and the HIV/AIDS epidemic. More importantly though, Hoang mourns the absence of gay Asian American sexuality in the surviving, whitewashed visual archive of late twentith-century homoeroticsim. His expression reveals the mixture of pleasure and grief experienced by queer subjects whose erotic history has been discraded and replaced by a white geneolgy.

For Hoang, the spiritual—now turned spectral—not only confers disparate feelings of grief and pleasure, but allows affected subjects to upend a linear progression of time by joining the past and present via his similarly hybridized body. By representing himself as both a contemporary viewer of Superstar and as a ghost that haunts its footage, Hoang splits himself across two temporal settings, that of contemporary viewers and that of the gay past that produced the film itself. By way of his spectral body, the past and present are briefly brought into contact with one another, their union producing gaps in time where opposing feelings can briefly exist simultaneously.

K.I.P. suggests a spectral mode of spirituality that can tentatively bind multiple feelings and temporalities to one contained space. In it, the past proceeds into the present just as the present turns around to haunt the past. Hoang’s unique approach to spirituality thus offers itself as a promising tool for queers attempting to connect lost histories with present circumstances. However, it’s important to remember that this connection is loose and tenuous. Just as Hoang’s ghostly body can appear only weakly throughout K.I.P., so too is the connection generated between past and present unstable, faded, and at the fringes of our perception.

vi. block: a prophecy of what’s in your way

You are well acquainted with blockages. Not their dislodging or their coming apart like pieces of wet paper, but their stuckness. Their insistence to hold on tight.

You have experienced all kinds of blockages. Spiritual. Literary. Even intestinal.

When you were a toddler, you would shit yourself often. Once older—ten, twelve, fourteen—you continued to shit yourself. Last week while shopping for a book, your gut tightened, prompting your legs to twist into a familiar, awkward position that keeps your anus clamped tight. An embarrassing reflex written into your muscles.

At twelve, your parents take you to see your second gastroenterologist. Crying and humbly gay, you are bent over an examination table as the doctor fucks you. Not really fucks you. He doesn’t stick his dick in you, but he does what you’ve done to yourself in countless long showers, and later, you will realize how impossible it is to separate the unending shame of this moment from your unending desire to be touched.

Fingering an x-ray of your translucent gut, he makes a wide, circular gesture with both hands. The shape of the blockage inside you. He explains that after years of thwarted defecation, you have accumulated a large ball of shit in your lower intestine, the very ‘internal disturbance’ that your life of twisting pain has been built upon as the shit-ball pressed, pushed, and repositioned your small organs.

Oh my god the shit-ball. When you were very young you imagined that no one could ever love someone who shits in their pants. You look down at the drying swab of shit in your underwear and decide that you will have to hide this perfectly for the rest of your life. ‘What are you going to do,’ your mother asks, ‘how will you get married? How will you share your bed?’ You realize that in your underwear is the secret that all people will hate you forever.

I want to tell you that when you grow up your shame will have transformed into pleasure. Your anus made anew by the gentle rocking of Chris and Jason. But I can’t. Although you will conquer your dysfunctional defecation and your anus will, for the first time, be your ally, there is no untelling a prophecy. Your organs have already been inscribed with doubt and suspicion. You will have to mitigate the invisible line dividing shame from desire and wonder if it even exists at all.

You will introduce yourself to pain and I am so sorry. I am sorry that I am the person you are slinking towards. I am sorry that this is the history I have drawn for you and I am sorry that I abandoned you to run it ad infinitum. Although you know I am proud, I am so very sorry I have chosen to live life as a homosexual.

My sadness is immobile and begs for the shape of spirituality. It has a tendency to produce habits and confer disparate feelings. It can transform if only briefly, the erotic body into a channel for self-love, sadness, and understanding. I see spirituality as a possible opening through which I can reach you. I watch you through the screened-in door as you pet Amber, the cousin’s now-dead dog. Shaded from the green light by your shaggy blond hair and her soft fur, the two of you rest in the grass like frayed chew toys.

vii. blessing (again)

(please read aloud)

Blessed be He Who leads all sorrow to Heaven! Blessed be He in the end!

Blessed be He who builds Heaven in Darkness! Blessed Blessed Blessed be He! Blessed be He! Blessed be Death on us All!

—Kaddish, Allen Ginsberg (1961).

Footnotes

-

Ginsberg, Allen. Kaddish: and Other Poems, 1958-1960. [San Francisco]: City Lights Books, 1961. ↩

-

https://www.godhatesfags.com/signs/index.html. If you are a homosexual looking some for some wild shit, please look at this website. It is bonkers. There are posters, parody songs, videos, and hymns. I’d suggest getting your kicks and then quickly leaving. ↩

-

Wiman, Christian. Interview by Jessa Crispin. Bookslut, Mar. 2009, http://www.bookslut.com/features/2009_03_014174.php. Accessed 15 April 2021. ↩

-

Kingston-Reese, Alexandra. Contemporary Novelists and the Aesthetics of Twenty-first Century American Life. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2019. ↩

-

Cvetkovich, Ann. Depression: a Public Feeling. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012. ↩

-

Fratino, Louis. Getting Dressed. 2019, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., https://www.sikkemajenkinsco.com/louis-fratino; Invitation. 2019. ↩

-

Fratino, Louis. Interview with Sholeh Hajmiragha. Work In Progress, June 2017, https://www.workinprogresspublication.com/new-page-2. ↩

-

Fratino. May. 2020; July. 2020; The Manhattan Bridge. 2019. ↩

-

Fratino. Waking up first, hard morning light. 2020. ↩

-

Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2010, pg 96. ↩

-

Cvetkovich. Depression. 2012, pg 56. ↩

-

Fratino. Angel Writing a Letter. 2019. ↩

-

Cvetkovich. Depression. 2012. ↩

-

Fratino. Blowjob and Moon. 2019. ↩

-

Nguyen, Tan Hoang, and William Higgins. K.I.P. Vancouver, B.C.: Video Out Distribution, 2002. ↩

-

Freeman. Time Binds. 2010, pg 9. ↩

-

Freeman. pg 13. ↩