Thus Bespoke Zarathustra

Kevin Chu

I held out my arms like I was being patted down by a TSA officer. I stood facing forward while a man professionally trained to read body language stared intently at me, looking up and down my posture. But this was not the airport security line. I was in an artist’s loft in a gentrifying part of town getting fitted for a bespoke garment. A sliver of measuring tape wrapped around my chest, I watched my tailor move with purpose, mapping out my figure down to the difference between my left and right wrist circumference.

PJ was a third-generation tailor. He had worked as a Savile Row cutter, but we were as far from Savile Row as we could be. Apron and tailoring shears in pocket, unlike the overly slick slim-fit suits of department store and Indochino salesmen, he walked me through how I might want to design the bespoke blazer jacket I had commissioned him to make. I had come in with an idea of what I wanted, after watching a bunch of Gentleman’s Gazette videos and finding a reference design from Suitsupply. But PJ told me plainly: “The jacket you want me to make you is not going to work.”

Menswear has its own distinct visual vocabulary, he explained. Full canvas construction, lapel roll, mitered cuffs, single vs. double vents, Milanese buttonholes. For many, a suit is a suit. But why do some wear their clothes well, while others are worn by their clothes? It’s the details that matter. “How do you look like you know what you’re doing in the Macy’s men’s store? Walk up to a rack of suits and start inspecting the lapel fold or count the number of stitches per inch.” That is the first promise of tailored clothing: working with somebody whose professional interest is to make you look good. Someone who cares as much as if not more than you do about the details that make that possible.

The Suitsupply design? It may have photographed well on a slim, chiseled model, but it didn’t get the details right. It simply tried too hard. For instance, the jetted pockets: the most formal pocket type, reserved for tuxedo jackets, doesn’t belong anywhere on a blazer or even a suit. Or the all-too-serious shade of midnight navy that would be out of place for a summer or even three-season jacket. Meanwhile, the loose and unstructured Neapolitan spalla camicia shoulders, an odd contrast to the more formal elements, gave off more sleaze than sprezzatura. At least it didn’t have brass buttons, the tacky mark of the New England prep school fashion crime to war criminal pipeline.

In my back and forth with PJ, I deferred to his recommendations for the most part. He steered me away from subtle sartorial faux pas and made suggestions based on what would work with my body, and not that of a model.

We arrived at what would become a single-breasted navy jacket with a notch lapel to match, double vents in the back to account for how I liked to put my hands in my pockets, simple patch pockets to accentuate the less formal nature of a blazer, and a classic three-roll-two lineup of horn buttons dark enough to match my shoes. After flipping through the square flaps of fabric books with samples of wool that would eventually be spun and sewn into a three-dimensional drape, we agreed on a breezy hopsack weave from Vitale Barberis Canonico, the venerable Italian fabric mill that has been family owned and operated since 1663. Keeping in line with the Italian design language, PJ suggested that we look just a bit north of Naples. A self-professed fan of Brioni, he matched my upper body shape to the Roman fashion house’s style of more structured shoulders. Finally, a curved barchetta breast pocket.

After the course of a few months and a few fittings, I ended up with a really nice garment that came out to be significantly less expensive, yet of even better workmanship, than an off the rack designer suit from Bloomingdale’s or Saks Fifth Avenue. Even if nobody else noticed, I could appreciate the subtle hallmarks of skilled handiwork: the lightness of a hand-fastened collar, hand-stitched monogrammed initials, the birdseye Milanese buttonhole, cuff sleeve buttonholes that actually work, the barchetta (what a lovely word)—all time-intensive flairs that are only possible under experienced hands. Furthermore, I could speak for the provenance of the labor that went into it, from having met face-to-face with the tailor who did the design and fittings to it being sewn together by a local independent tailoring collective.

Should it be surprising that I was able to get a well-made, handsewn, and ethically sourced bespoke garment for way less than what one of comparable quality would have cost if it had a designer label on it? In the minds of the typical fashion consumer, there is only expensive aspirational luxury designer, or cheap fast fashion that lasts just barely long enough until the next Shein haul.

People can get really weird about defending their right to shop from Shein. “I know its impact on the environment. “I know how they treat their workers. But honestly? I don’t blame myself for shopping there when my options are so limited,” said a commenter on a Reddit community for plus-sized people, lamenting their difficulty in finding clothes in their size from anywhere other than Shein. “I also don’t blame myself for wanting cute clothes.” They insist they have no other choice. “Selfish? Sure, but when the whole system is rigged against people like me, I think we should be allowed to be a bit selfish.” But is anybody forced to buy from Shein? Is it classist or even fatphobic, actually, to shade people for buying $6 tops made artificially cheap by child labor? Of course not. Shein discourse is consumerism made woke: Spending money on nicer things is elitist, while buying hauls of shit-tier clothes at cheap prices made possible only by labor exploitation is smart and thrifty.

But how much can ethical fashion solely be a matter of personal responsibility? We might not be having the same conversation around ultra-fast fashion in the first place if consumers had more options of where they can get their clothes from. It turns out that in many parts of the world, tailored clothing is perfectly normal. This is only made possible by a robust infrastructure of garment makers and a healthy, diverse fashion ecosystem that affords people a spectrum of choices other than buying from the same mass-retail megabrands.

You can find tailors and cobblers in every neighborhood in Italy, where it is nothing more than a small errand to stop by the tailor shop every so often for small things like getting a button replaced or a sleeve tapered. Hong Kong’s vibrant tailoring community, known for the 24-hour suit (the original fast fashion), owes much of its heritage to Indian Hindu immigrants who fled the Sindh region of what is now Pakistan in the aftermath of the Partition. Such places simply have a lot more people in the clothing trades. As a result, handmade and tailored clothing is that much more accessible to regular people. Such is the fruit of an established sartorial culture that respects and normalizes tailored clothing. Meanwhile, here in North America, the lack of such infrastructure and cultural norms to make quality clothing widely affordable and accessible relegates tailored clothing to a novelty at best, snobbery at worst.

My zillennial generation remembers iCarly nemesis Nevel Papperman (“You will rue this day!”) and his obsession with menswear. His lifelong dream to open a haberdashery serves as an additional layer of characterization to his arrogant and pompous personality. The joke lands because formal clothing has become synonymous with out-of-touch elitism. But even if dressing up is a rare, eye-turning gesture nowadays, dismissing it as elitist is ahistorical.

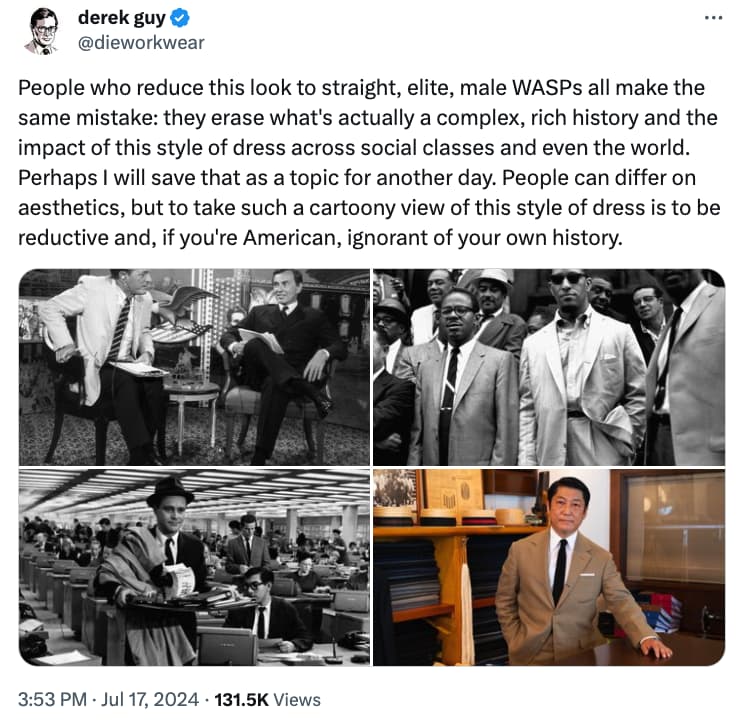

Even the classic Ivy League style of menswear, nowadays better known to the TikTok generation as part of the “old money quiet luxury” aesthetic, was not the exclusive preserve of old money Ivy League polo guys. “People who reduce this look to straight, elite, male WASPs all make the same mistake: they erase what’s actually a complex, rich history and the impact of this style of dress across social classes and even the world,” said Derek Guy, the extremely online menswear commentator known as “menswear guy” on Twitter. “While many of the people who gave this style its meaning were WASP, the tailoring was done by Jewish immigrants. Black jazz musicians also gave the style a sense of cool.”

Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style chronicles the subversive role of classic Ivy fashion, adopted to signify both respectability and rebellion, in Black cultural and civil rights history. Wrote authors Jules and Marsh: “Style is about the freedom to be oneself, to authentically express oneself, and in doing so reject limitations imposed by others. A consciousness of style, in essence, emerges when one asserts one’s right to self-definition and the right to take control of one’s own Identity.” In parallel, David W. Marx’s Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style traces how Ivy style gripped Japan’s national consciousness and the ensuing ripple effects on fashion as we know it today.

What would it take to get more people to care about clothing again? Menswear guy has observed that “many people are not actually into clothes. They are into fame, rich lifestyles, and certain body types.” Slim fit and vanity sizing prey on purchasers’ insecurities and force people of varying body types to fit into a narrow range of predefined shapes and sizes. Luxury labels and fast fashion retailers alike tap into the drive for aspirational consumption. Lacking in meaningful community ties that would otherwise provide a sense of identity, atomized and overworked customers go into credit card debt for aspirational purchases that they hope will say something about who they are. A new handbag or sports watch, as a treat. Another Shein haul, for the gram. Perhaps the second promise of tailored clothing then, is to grant you some reprieve from all of that by making it about the clothes again.

As somebody who lives and breathes Uniqlo-core, I wasn’t one to find myself in front of a tailor. The last and only time I bought a suit was in high school from Men’s Wearhouse. What drew me down the tailored clothing rabbit hole was how rich and personal the experience can be. I appreciated the interpersonal aspect of being able to put a face to who made your clothes. I found the lore behind fashion history and etiquette fascinating. And of course, I developed a respect for the craftsmanship of the clothes themselves.

I liked that tailored clothing was a conversation that unfolded over months, unlike a one-and-done transaction after a few clicks or swipes. The magic of tailoring happens during the fittings, the first of which is a test of how well raw measurements and a quick croquis sketch translate into an actual half-finished garment draped over your figure. It continues as you further iterate on the fit of your garment under the discretion and judgment of a real person who is really good at their craft. Meanwhile with fast fashion, the fitting process starts and ends when you try on your $6 top in front of your bathroom mirror only to realize it cannot possibly fit you in any flattering way and subsequently condemn it to a landfill somewhere.

Embracing clothing as deserving of your attention and respect changes not only how you dress, but also how you view yourself. The ethos of tailored clothing rejects insecurity for exploration and experimentation. It instills patience and delayed gratification in the knowledge that beautiful things take time to create and are worth waiting for. I liked how Mark Cho, one of the best-dressed men on this planet, put it. “We want people to know the joy of well-made things that age well. We want people to know how clothes are made and how to wear them. And most importantly, we want people to understand their style,” said Mark in an address celebrating ten years of his men’s clothier The Armoury. Regardless if you have tailored clothing in your closet or not, it’s worth giving a damn about how you dress and carry yourself.