Hey MTV! Welcome to our crib!

Phoebe Pan

i. tchotchkes galore

The scene: a wall of shelves, stuffed and neatly lined with vinyl records. A leather armchair, vaguely Scandinavian in design. A thin, long desk (maple? oak? either way, the grain is pretty). A wooden foot with a spider image engraved in it from Laos. A Swiss flag mug. Stubby pencils kept in shot glasses. A bobblehead figure of Yasuhiro “Ryan” Ogawa.

Haruki Murakami’s workspace has gained something of a cult following: rewind back to 2015, at the height of Tumblr days, when his website won a Webby award for best self-promotion/portfolio. I remember my own obsession with it, as well as my vain attempts to imitate his aesthetic, from keeping a mug of stubby pencils nearby to lining the corners of my desk with swim meet pins and beaded prayer bracelets. (The record library, of course, was a pipe dream, so I stuck to building my iTunes library of YouTube videos converted to mp3s.) Though I can’t say that it helped me write any better, poring over Murakami’s workspace inaugurated a practice that involved hours of compiling digital folders overloaded with clipped #deskinspo content, scouring Japanese stationery sites for organizational tips, searching for… well, the perfect workspace.

Over the years, I have been trying to understand my obsession with writer’s rooms, painter’s studios, and generally a type of interior deco aesthetic that I can only describe as every Pinterest user’s dream of a “rustic artist’s retreat.” I can’t even call it embarrassing, at this point; I have fallen in love with so many rooms not of my own, partly because I wanted something in the likeness of those spaces, partly because I found something hallowed in the way those spaces felt like the people who lived in them. Ursula K. Le Guin’s study, where she kept trays of rocks from her travels; Criterion’s artist studio tours; the curated kitsch of the Nowness “My Place” series; even Mahler’s composing hut, incongruously situated next to a modern petting zoo. Frequenting these rooms, I thought often of what Gaston Bachelard calls the poetics of space, and the way attics, bedrooms, living rooms are our first universes and corners of existence. Dwellings are what furnish our daydreams and ventures into imagination with safe passage: think, perhaps, of the way you might huddle into a reading nook like a rabbit in its burrow, or a bird in its nest. Yet Bachelard does not touch upon the strange duality of the work space—I realized that as much as I desired comfort at a desk, I also desired the unknown, the spark of risk that flashes across the mind while engaged in exertion.

A part of me wonders if this casual obsession with workspaces is really an interest formed at the crossroads of aesthetics, labor, and environment. Elaine Scarry writes that beauty begets replication; what of the urge to replicate a workspace? To be transparent, I don’t intend to provide definitive answers here, and have shied away from a formal “academic” approach to thinking about workspaces, with a few literary exceptions and examples. Rather, I want to present this essay as the hypothetical desk where we meet, on which I have gathered an armful of examples and questions, through which we can begin to sort and comprehend what workspaces actually mean to me, and to you.

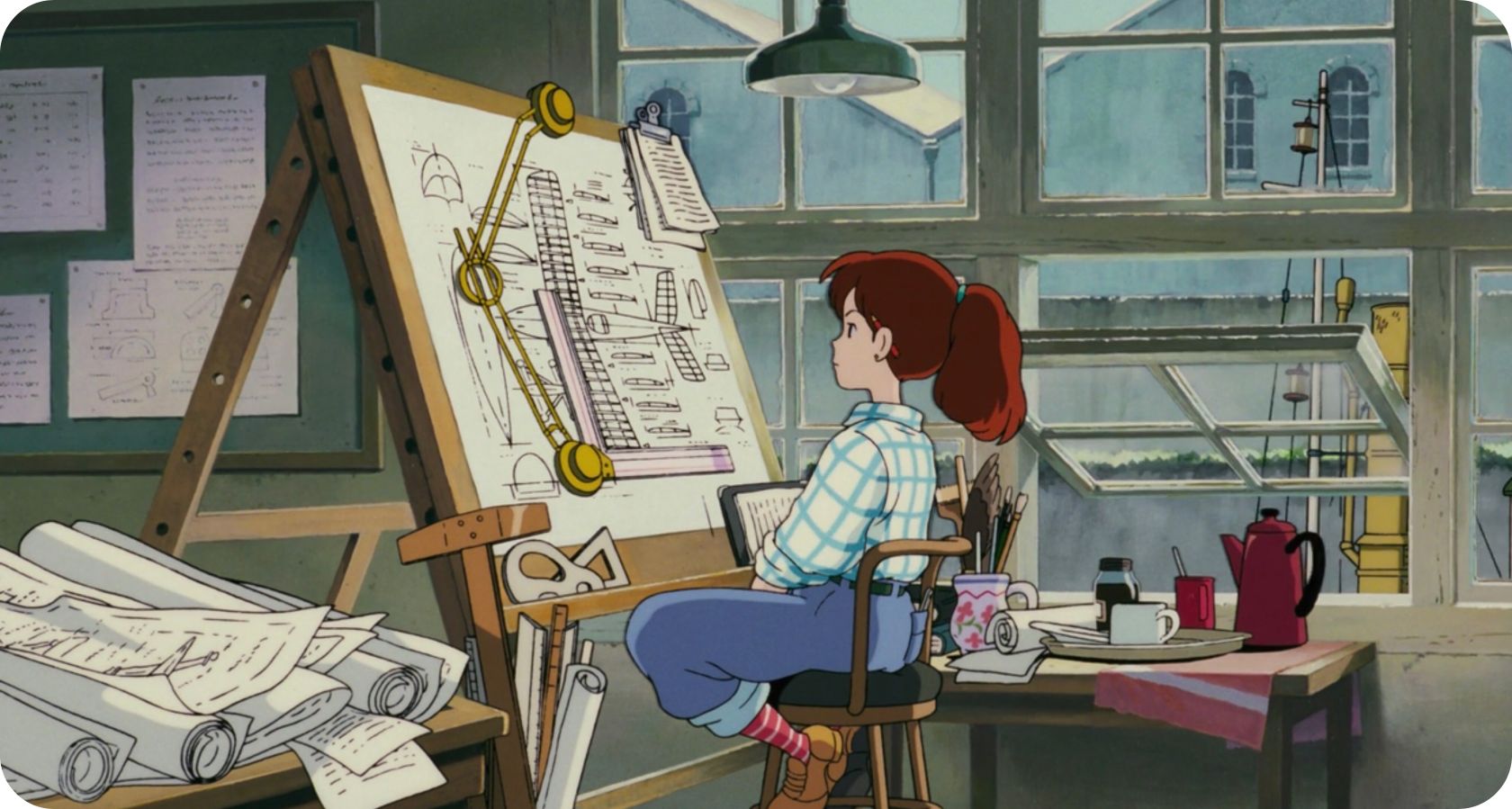

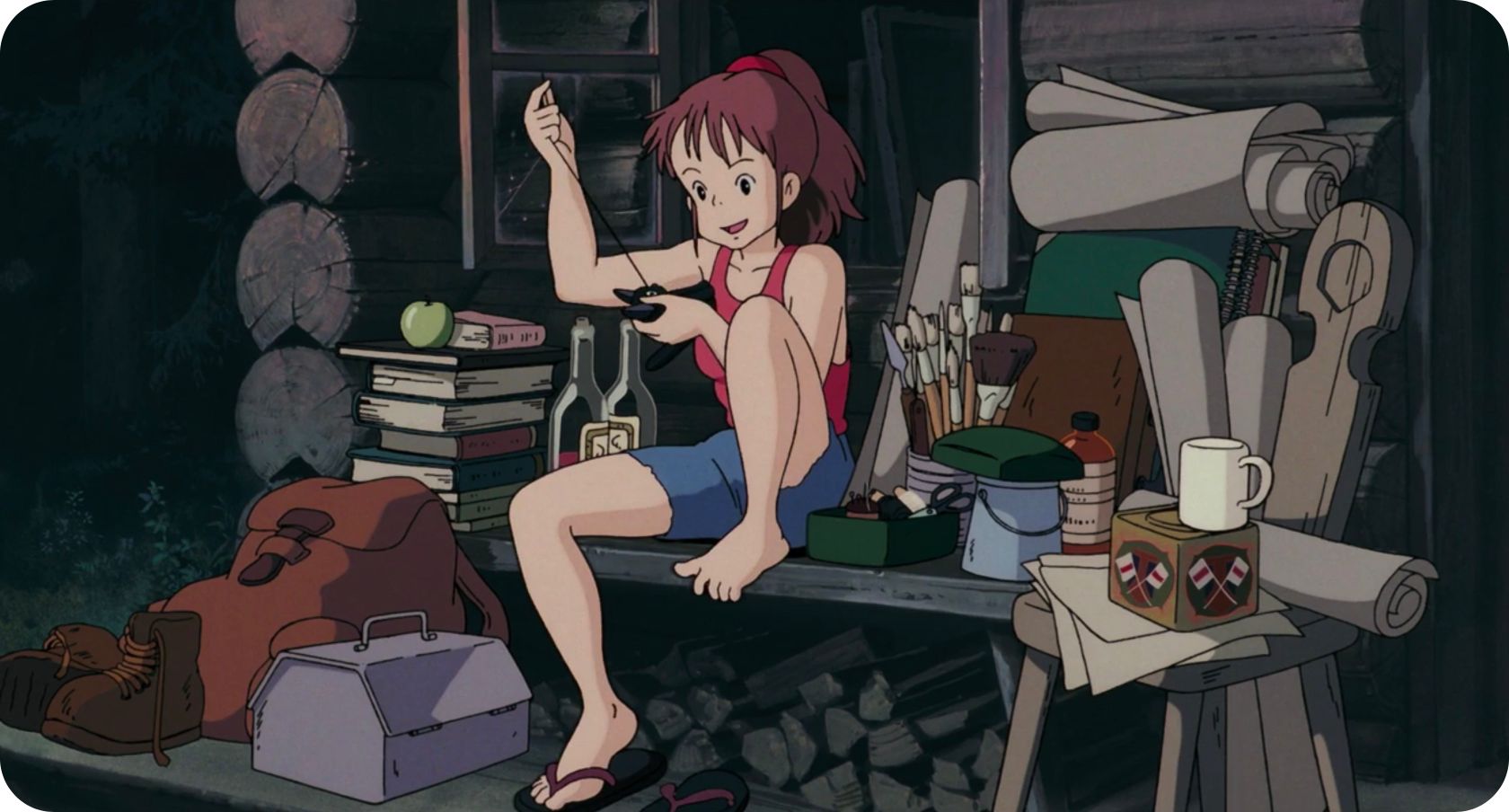

To start, I’ll turn, in particular, to Ghibli films, of which I am often mulling over, and the way that they aestheticize labor to make the act of working seem somehow alluring. I grew up watching many of these films as necessary comforts, and I did not realize until recently how much I had subsumed their philosophies into my life, especially the way that they portray characters being “immersed” with regards to one’s work. These fictional workspaces shuttled me back and forth between various characters’ deep absorption in their environment and my own encounters with a type of studious calm, observed in real-life counterparts—

—the garage where my dad worked on his car, the space where he could blast music on speakers and wrench bolts and wipe the grime off his hands with old t-shirts repurposed into rags, and would sometimes pop his head through the front door and ask if I could get him a glass of iced water on the warmer summer days—

—my junior year dorm room, wedged into the shape of a 15-foot U-haul truck, with my desk at the window and bookshelves along the wall behind my chair, where I would scribble essays and cry silently about crushes and ponder purchasing my own electric kettle so I wouldn’t have to walk down the hall to the communal kitchen for a cup of hot tea—

—art classes, my sister’s sewing space, visiting open studios and marveling at the scrolls of paper, brushes, bottles, mugs with paint water & mugs with drinkable water (all indistinguishably brackish), drawers and buckets of supplies, drafts taped up on white walls, desks, some of the most beautiful, wide wooden desks I’ve ever come across—

—the personal libraries of mentors, professor’s offices, crammed with books and old lamps, shelves separated by genre, shelves crowded with genres, zine piles, newspaper stacks, my grandpa’s study where he keeps his spiral notebooks that are puffed up from years of Bic ink pressed into their pages.

A few zines ago, Lauren and H.Z. made a piece on inhabited spaces and the different lenses through which we can interact with and view them. I want to think phenomenologically alongside their drawings, in terms of where the body meets the world and where we can begin to uncover the resonances of spatialized existence. With regards to the workplace, it might be easiest to begin at the center of gravity—a desk, perhaps. There are other variations, too: I follow Kenji López-Alt’s cooking videos on Youtube and think often about his home kitchen, especially its meticulous, organized chaos and the way Kenji intuitively reaches for spices, spoons, bowls, ingredients to bring to his cutting board and stovetop burners. A workspace’s center of gravity doesn’t necessarily have to be an office desk; it can be whatever constitutes the central meeting point of your workspace, where most of your activity gathers.

Even when a workspace might not have a readily discernible center of gravity, the allure of its environment seems to shine through the intimate object relations of one’s surroundings: consider the International Space Station, its labyrinth-like interior and its writhing masses of wires and cables, cluttered to the untrained eye and yet carefully organized to those who inhabit it day by day. There is, perhaps, something beautiful about a space that appears clunky and unattractive to anyone but yourself: an eros enacted through space, through your own orientation toward objects, through transparent relations that can only surface as secrets to others.

I’ve recently started the process of building my own bicycle from the frame up, and with that, have transformed one corner of my apartment into a mess of bike tools piled in a little multipurpose Ikea bucket. No fancy bike stand, no work station—just my bike leaned against the wall, and the bucket of tools, and the occasions where I have drawn up a stool, fiddled with parts, played Charli XCX in the background. I’ve always dreamt of what it’d be like to work in my own garage space for tinkering and building, or even a shared, dingy basement shop like a college bike co-op. Yet even the scattered, cramped nature of my makeshift bike station in the apartment has its charms, for reasons that only I can articulate from the hours I have spent hunched over, assembling brake parts, disassembling bottom brackets, installing pedals.

In his essay “On Beauty and Being Home,” literary critic Jonathan Kramnick unpacks the occurrence of the word “handsome” in Robinson Crusoe, a word that he reads as referring to both an aesthetic evaluation as well as the quality of being “at hand,” near and palpable. In Kramnick’s reading, Crusoe practices embodied aesthetic perception, fashioning for himself a crude yet “handsome” habitat, complete with a table, chair, baskets, shelves. The handsomeness of Crusoe’s habitat appears out of recognizing a kinetic interaction with one’s environment and the ways in which skilled action can alter the encountered world. As Kramnick notes, Crusoe’s handiwork has strong ties to the haptics of Georgic, locodescriptive eighteenth-century poetry: the beauty of needlework, for example, “that takes shape from the end’s of one’s fingers.”

I offer this literary digression to muse on how and why we might find workspaces beautiful or alluring; to return to Bachelard, perhaps there is something poetic about organizing a space for the purposes of movement, whether bodily or through the motion of thought. In Kramnick’s usage, aesthetics is not an evaluation marked by mass consensus of an audience, but rather determined by the individual who encounters beauty through an intimate, embodied relation to the world around them. We see this in poetry, often: poetry as an examination of intimate spatial relations, refracted here, in the case of workspaces, as the possibility of inhabiting space to be a poetic act. In other words, when Seamus Heaney writes:

The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft Against the inside knee was levered firmly. He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep To scatter new potatoes that we picked, Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

—we might think of the way work appears in these lines, body and environment enmeshed, adjacent to Heaney’s descriptions of his pen as a spade, where we might reimagine a desk as a plot of dirt and words being excavated as apples of the earth. There is something deliciously tactile in Heaney’s lines that resonates with how I experience a good workspace—the joy of having things at hand with which to work and interact, even if stripped down to the minimalist features of the textured grain on a wooden desk and the cool hardness of a laptop resting atop. Here, a workspace might emerge as a place where one realizes the beauty of labor, and specifically, a type of artisanal labor that involves skill and craft, shorn (if temporarily) of monetary, economic barnacles. A labor of love, as they say, deriving from a space that reminds us that techne (craft) and episteme (knowledge) are not as divorced as we have made them out to be.

ii. a room of our own

So far, I’ve been tending to workspaces in the idiosyncratic, personalized sense, reflecting spaces where a person at work tinkers their desires and imagination into material form. From here, I want to begin to think about workspaces of the public variety, more commonly associated with office cubicles, libraries, cafes, conservatory rehearsal rooms, and the like—workspaces that aren’t marked by an individual’s curation of the space, but by a kind of anonymity that allows you to spread your work out and then pack it up without so much of a crumb left behind. (Though, one might also note the occasional messages and notes scratched into carrel walls, professing existential malaise and Sapphic fragments left to the whims of imagination.)

Even the broader concept of a dedicated “workspace” is puzzling: why relegate one space for work when, for many, work happens across a broad spectrum of locations and environments? There are creative constraints that can come with working in a space that isn’t fully yours, especially in publicly marked workspaces, where there is a kind of atmospheric pressure to avoid distraction and be “productive.” There is also the issue of romanticizing a dedicated workspace, when, materially, that option may not be financially attainable for most. Virginia Woolf may have written an eloquent case for a room of one’s own, yet as many have pointed out, not all writers can afford rooms of their own. We might instead take Woolf’s adage in the metaphorical sense, in a similar way that we might think of Sara Ahmed’s spatialized tables of feminist killjoys. A room, a desk, not as a material prerequisite for creativity or work, but as a conceptual space around which we orientate ourselves.

What makes a public space “productive,” then? Is productivity, in the capitalistic usage, even the goal of all public workspaces? Take a library, for example: a space of quiet, where you are surrounded by books and desks and the occasional scrape of chairs against floor, the shuffle of papers and clack of keystrokes. The aura of productivity that emanates through a library seems vastly different from the aura of productivity that emanates from a cafe, or an office lounge, and yet all these spaces share the intention of offering space as an oasis for production and thought, where you can, simply, get things done alongside others.

Perhaps it’s not even a strict sense of productivity, then, but rather a type of performativity that one participates in while inhabiting a public workspace. To return to literature, it might be useful to think of workspaces in the theatrical sense: a space within which you understand that others may be witnessing and/or surveilling your actions. I’m reminded of Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, a play whose set is austere and spartan, stripped down to a bare floor and uncurtained windows. At the center of the stage, a single large table acts as the stage within a stage where objects of importance appear and encounters unfold between characters; the books, magazines, and portfolios placed on the table become the objects that make visible to the audience the feelings and emotions and time that remain obscure to the naked eye. Indeed, public and communal workspaces tend to be more minimalist rather than maximalist, their tables shorn of tchotchkes to allow room for your own papers and pencils. A public workspace, such as the counter at a cafe or the carrel at a library, becomes the tabula rasa on which your thoughts appear, temporarily, in a communal sphere.

Surveillance, of course, registers ominously when put toward capitalistic ends: employment tracking, management systems, often intended to force people into the roles of productivity machines. Yet I have worked in few traditional office spaces and cannot speak to the exploitative affects of those particular stages; I have, rather, a somewhat skewed view of the more optimistic possibilities of public workspaces. Libraries, for instance, are the spaces where I learned to write essays and poems, where I fell in love with dozens of novels, where I began reading newspapers and serials, even if only because I saw others doing the same, deep in thought and reflection. The performativity that I encountered in those public workspaces was aspirational, not to profitable but to creative ends—the type of performativity that involves you and strangers acting out a play onstage not because you necessarily believe in what the play will produce, but because you believe in the act of performing alongside others. Say something enough times and it begins to become true; pretend to work enough times alongside others in public and the work begins to be true, as well.

There are also spaces, such as tattoo collectives, or community art studios, that are deliberately collaborative and shared workspaces, thriving on improvisation and intimate proximities to others’ creative endeavors. These types of spaces bring to mind how any workspace, at its core, is about a practice of relationality—all these books, CDs, and magazines as the things toward which you turn and relate to. In the case of working alongside others, at its best, the communal workspace manifests feelings of solidarity, of falling into solitude with the comfort of knowing that others around you are doing the same.

Yet even as I try to delineate private and public workspaces, it has become increasingly difficult to separate them: the open office plan, the Studyblr personal desk space, park benches and student lounges, where the “productivity” of workspaces can blur with friendly conversation and socialization. I wonder, too, about the vague horror that is Apple Park, the suburban office that is at once a corporate headquarters and a nature refuge. Within that space resides a forced collaborativity that feels antithetical to the spontaneous collaboration that occurs out of artistic communal spaces like Soft Surplus; perhaps it is that any space marketed as “creative,” shorn of true artistic intention (whatever that means!), feels hollow and artificial.

For me, the problem with spaces such as Apple Park is their lack of integration into surrounding communities. Apple Park, alongside every other less fanciful and costly rendition of a corporate office workspace, is decidedly not for the public—it is for, rather, its employees. A building—no, a park—designed in the middle of a suburban space, even if it is not designed for individual use in the way that an iPhone is, still matters to its community by way of the sheer spatial footprint that it marks in its surrounding geography. Contrast Apple Park with something like the Central Seattle Public Library (which is, in my humble opinion, architecturally so much more sexy than Apple Park), equipped with everything from music rooms to lunch tables to free Wifi. After all, why create a public workspace when it is not, truly, for the public?

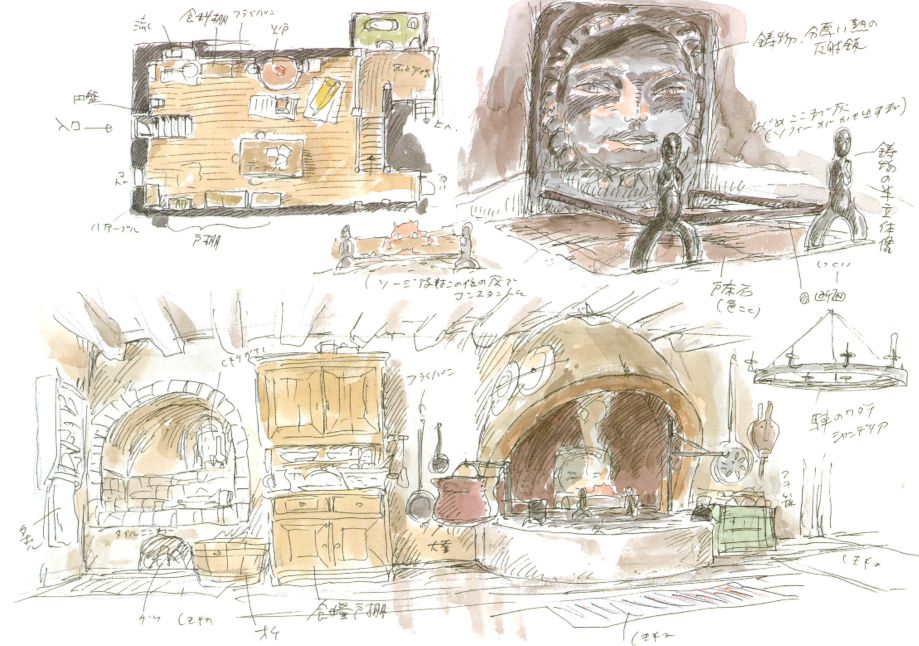

iii. howl’s moving castle

Circling back to the nuances of private-public workspaces, I wonder if it would be more helpful to think of the workspace, in general, as a mobile conception; the workspace as hybrid monstrosity that collapses the public and private. Returning to Ghibli spaces, I have in mind Howl’s Moving Castle, visualized as both home and workplace for Howl’s magical exploits. What fascinates me is the aspect of mobility in his castle: that his door can open up to a number of different geographical locations, that his castle is cobbled together in such a haphazard, junkyard way such that magic is the only thing holding it together.

There are fantasy workspaces, too, of the lo-fi beats and ambient variety. As with many internet phenomena, these vids exist in the murky space where the personal meets the collective: they are nobody’s and everybody’s workspaces. Time stretches into Sisyphean dimensions. The lo-fi girl (who began as Shizuku from Studio Ghibli’s Whisper of the Heart) works in an endless loop of studying, turning page after page in some infinity journal and every so often glancing out the window (at what? for who?). These spaces thrive on borrowed desire, assuming that the more you study with them in the background, the more likely it will be that their diligence will rub off on you.

What does it mean, then, that we converge on this non-existent space of the lo-fi girl’s desk to call our own? The aspirational dimensions of these fantasy workspaces walk the dubious line between pleasure and productivity: here, we return to aesthetics of labor, and the ways in which these fantasy spaces make work look good. Margaret makes an excellent point in her essay on the cult of the lo-fi girl: “The Lofi Girl aesthetic might be said to be about maintaining sanity in the face of never-ending pressure to produce. Insidiously, it might also make those demands seem more humane when in fact they eat away at the boundaries between work and personal life.” Yet to this, I would gently ask, with genuine curiosity: at what point did it become necessary to separate work and life? Is the separation more necessary in the temporal rather than the spatial dimension? There is something to be said about preserving spaces in which meaning does not rely on capitalistic forces of productivity and labor—but I am also thinking of other realities and the early modern poets and writers I study, for whom work and life had not concretized into separable entities, for whom work and life were not necessarily opposed but rather constitutive of one another.

The peculiar aspect of the fantasy workspace that transforms work into lifestyle is also a sentiment that evokes artistic and creative practices. When artists speak of “living with and through their work,” I don’t always take that in the negative connotation of an absence of work-life balance: at times, the phrase can refer simply to the act of conceptualizing work as an ongoing practice of attention. As opposed to “optimizing” a particular workspace to facilitate a linear, efficient path from start to finish, living through work makes room for meandering, thinking, and improvising with your tools at hand, wherever you may be. The hybrid monstrosity that is Howl’s Moving Castle isn’t meant to be a celebration of capitalistic, corporate work turned into lifestyle; the whole ruse of the castle is that it’s difficult to locate and track. It’s a celebration of how messy and ongoing true work can be, the type of work that we maintain outside of surveilled institutions, the type of work that fuels the aphoristic fire in our hearts, no matter where or why we’re doing it.

Last summer, I would often spend long days with my partner at her Brooklyn apartment, usually staying over for a few nights at a time. She had a tiny, cozy bedroom, but there was no space for a desk. At the time, I was working remotely for a literary summer camp, so I would work from her bed whenever I stayed over. Camp began at eight in the morning over Zoom, so I’d set up my little corner and sit cross-legged, laptop perched either on a stand or a precarious stack of books, with a mug of tea on the dresser nearby. It wasn’t ideal, but it was pleasurable, because I cared about the work I was doing, and the odd conditions made me think differently about my relation to my environment (my posture, the way I had to take care when stepping off the bed, the way that leaning against the cold wall actually felt quite nice in the summer heat, the way I would be more conscious of getting up to stretch and move around because my body wasn’t used to sitting in a cross-legged position for long periods of time). It was confusing to inhabit the bed as both a place of work and rest; yet it was also delightful to realize that I could still make bad puns and recite lines of poetry to kids despite the bizarre, untethered nature of my ambiguous workspace and their non-corporeal internet presences.

Do you need your own dedicated workspace, à la Mahler’s hut or Murakami’s writing room, to work? Certainly not. Those types of workspaces can be significant, and I won’t understate how satisfying it is to make a space of your own, especially with the kinds of work that require more tools and space (i.e. car repair, sculpting, bicycle maintenance, etcetera). But there are plenty of examples a portable work station could be modeled from: plein air painting, laptops as mobile cabinets and notebooks, theodolites used by surveyors. A defining feature of the workspace may be the ability to create a private bubble within which your thoughts can roam comfortably, yet that bubble is always situated in a broader sense of community and the public: what would it mean for your environment to be a part of your work, then? How would a mobile conception of the workspace allow us to think more critically about the way that we relate to objects and environments around us, as well as the intentions we set out, the structures of thought and action that we build wherever we reside?

Perhaps your workspace is only as suitable as your aesthetic and ethical relation to the world around you, and the way you move through the world as such. Wherever it may be, the workspace becomes the place where our private thoughts and intentions meet and collaborate with the material, felt world around us. Now, I’m fortunate enough to have my own workspace: a long and wide dining table repurposed into a desk on which I can spread all my books and papers. Even so, I still think about relationality through the books that gather next to my keyboard, the figurines that others have given me on my desk, the pens collected over the years. The window nearby overlooks a parking garage and the back alleys of apartment complexes, framed by vines of telephone wires; the sunsets, even from this view, are lovely. There is a bit of every past workspace in my current one, from the library carrels, the cafe bar counters, the park benches, the dinner tables of friends, the seat trays on trains, down to the keyboard that I have kept since high school.

A place to think, a place to gather, a place to share. What is the perfect workspace, after all, other than the desire to find, with others, a space in which one can make meaning out of work, and a space in which work can be, through the sheer will of fantasy, something akin to beautiful?