The cult of “music to work to”

Margaret Schnabel

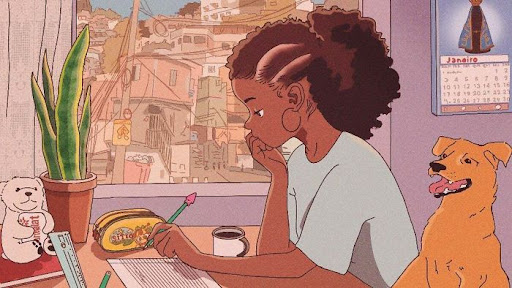

The world’s quietest cult leader sits at her desk sporting chunky retro headphones. The corner of a laptop is visible from our vantage point, but she’s not using it. Instead, she’s writing by hand—filling up roughly half a page before flipping to the next. Every few seconds, she looks over at the brick-red cat perched on her windowsill, which affably twitches its tail.

Allow me to introduce you: this is Lofi Girl, the focal point of hundreds of hours’ worth of background-music videos on YouTube. You will find her gentle companionship during your most vulnerable panic-work hours comforting, and then seductive. And then you will want to become her.

As I write this, I’m listening to the Lofi Girl channel’s twenty-four-hour “lofi hip hop radio - beats to study/relax to.” It is precisely the entanglement of those two modes—“study” and “relax”—that intrigues me, and that, I’ll wager, has contributed in no small part to the channel’s 10.3 million subscribers. The channel, originally named “Chilled Cow,” started a 24/7 livestream of lofi hip-hop music in February 2017. Its owner Dimitri, a Paris native, lifted a GIF from the Studio Ghibli movie Whisper of the Heart, whose protagonist Shizuku Tsukishima spends her free time writing in her bedroom. After copyright concerns, Dimitri put out a call in September 2017 for a replacement image: “a student busy revising for her classes with Miyazaki-esque visuals.”1 Colombian artist Juan Pablo Machado sent in the winning design, bringing Lofi Girl into her present incarnation.

The 24/7 live stream is flooded with warm earth tones, from Lofi Girl’s forest-green sweater to the red of her chair. Plants sit at her pleasantly cluttered desk. It’s clear that someone has taken pains to make the scene appear convincingly home-y.

This homey, unassuming aesthetic belies Lofi Girl’s wild popularity; the channel has a total viewership of nearly one billion,2 and at least five people have tattooed her likeness on their body. In fact, curated intimacy might be the key to her cult following. “I’d assumed that the video stream was important to a small but dedicated group of people,” recounts Sophie Atkinson in an essay for Dazed. “It was like finding out that the weird noise band I liked was actually the Beatles.”3 Indeed, the Lofi Girl account encourages viewers to see themselves as part of an exclusive group: the description for a “4AM Study Session” video reads “It’s that time of the night again, when everyone is asleep, except for a selected few who are still studying, vibing, and thinking about life.”

If this is indeed a cult, its values are clear: keeping insane work hours allows one to accrue cachet (even if, ironically, no one else is awake to offer it). The Lofi Girl channel touts one-hour “Study Session” videos from 12AM to 4AM. Night hours are especially fitting; there’s an intensity to working when one should be asleep, but the environment at those hours is private, often strangely peaceful. The “1AM Study Session” video finds Lofi Girl on a confusingly tranquil and highly decorated balcony, surrounded by both a modern cityscape and a starry sky. The scene is a patchwork of contradictions; it’s windy enough to rustle a curtain visible on the right side of the screen, but not enough to disturb any of the papers she has left completely free on her desk. It’s warm enough for her to study outside, but cold enough for her to drape a blanket over her shoulders. In the “2AM study session,” it’s snowing and Lofi Girl is perched in a comfy-looking armchair; by 3AM, she’s composed a blanket fort in her attic and I am wondering, as you might be, how an apparently single student can afford such spacious lodgings.

But I digress; what most interests me is what vision of work that these images (and soundtracks) put forth. In the opinion of Indoor Voices’ Nick Quah, Lofi Girl “has become kind of a short-hand for a certain kind of digital artifact that expresses this very specific cultural moment, which I suppose you can broadly described [sic] as the Venn diagram overlap of minimalism, work productivity-mindedness, cultural commodification, and SMOOTH JAZZ.”4

But what, exactly, does this “Venn diagram overlap” express about the current cultural moment? Let’s turn to cultural theorist Sianne Ngai, whose 2012 book Our Aesthetic Categories singles out three of the dominant aesthetic labels audiences apply to contemporary work: interesting, cute, and zany. Under which category might Lofi Girl videos fall? Not “interesting”; the music is intentionally repetitive and lulling. Even Lofi Girl does not appear to be interested in her own work; the video’s GIFs depict her frequently glancing off and yawning. Likewise, the videos (and the work they depict) are measured and contained, a far cry from the overactivity that characterizes Ngai’s description of the “zany.” The Lofi Girl aesthetic seems closest to “cute,” then; indeed, its origins in Miyazaki-esque visuals mesh well with Japan’s kawaii culture.5

Ngai theorizes cute objects as inciting a desire to consume: to make them our own. When a cute aesthetic becomes a commodity, we can own it; but insidiously, as Ngai notes, it also owns us. In Lofi Girl’s case, this means directing our vision of what sort of workers we should be. When work is shrink-wrapped in cute packaging, it becomes easier—even desirable—to bring it into our personal lives, our homes. Lofi Girl works on her bed; if she becomes our companion, and we eventually yearn to make her aesthetic our own, we may end up working on our beds, too.

Lofi Girl does not experiment; she does not get frustrated with her work or herself; she dutifully continues. She is not doing groundbreaking research; she is maintaining. Her work will never be done but instead continue in an endlessly looping GIF of obedient writing and reading. The Lofi Girl aesthetic might be said to be about maintaining sanity in the face of never-ending pressure to produce. Insidiously, it might also make those demands seem more humane when in fact they eat away at the boundaries between work and personal life. Why, dear reader, would you need work-life balance when the most aestheticized, desirable version of yourself brings work into your home? The cult of “music to work to” makes bleeding those boundaries into one another seem palatable, desirable, and, most importantly, safe. It’s for, to return to the video description mentioned earlier, “a select few who work and chill”—both, together.

Footnotes

-

Japan Nakama, “The Evolution of Lofi Girl”

https://www.japannakama.co.uk/the-evolution-of-lofi-girl/ ↩ -

YouTube official blog, “The Rise of the Lofi Girl” ↩

-

Sophie Atkinson, “The ‘24/7 lo-fi hip hop beats’ girl is our social distancing role model,” Dazed ↩

-

https://indoor-voices.blogspot.com/2020/03/did-she-always-know.html ↩

-

Despite Lofi Girl’s rigorous study routines, the kawaii aesthetic emerged from student protests in late-1960s Japan. “Rebelling against authority,” recounts Hui-Ying Kerr, “Japanese university students refused to go to lectures, reading children’s comics (manga) in protest against prescribed academic knowledge.” https://theconversation.com/what-is-kawaii-and-why-did-the-world-fall-for-the-cult-of-cute-67187 ↩